Hearing through the silence: a deaf child’s education experience

By Jonas Sijbrant and Mateo Golomb | February 1, 2024

Alumni

source: SCOT SCOOP, Carlmont High School’s Student News Site, January 30, 2024

When Ben Rhazi was 2 years old, doctors discovered that he was profoundly deaf.

As a result of being born with a progressive hearing loss gene, his inner ear lost all of its hearing function revealing he had sensorial hearing loss. Ben’s parents felt lost after they discovered his new challenges, they felt they had nowhere to turn for support in raising a deaf child.

“I still remember being numb when hearing that Ben was diagnosed as being profoundly deaf. We had a big decision to make on behalf of Ben- keeping him in the deaf society or implanting him so he can learn to speak,” said Irene Rhazi, Ben’s mother.

Although this may sound surprising to most, one out of eight people above the age of 12 are hard of hearing, according to the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

In the past being deaf had no possible “cures” as there was no solution regarding restoration of the hearing capabilities within the ear.

However, recent strides in technological innovation regarding the development of more advanced hearing aids and cochlear implants have provided a way for those who are hard of hearing or deaf to hear.

One of the children who benefited from the widespread popularity of cochlear implants was Ben Rhazi, who attended Hillsdale High School and is now pursuing his college education at Oregon State University.

Ben’s parents decided that it would be best for Ben’s future to have cochlear implants so he could eventually learn to speak and hear fully.

Following this, his parents discovered The Foundation for Hearing Research while looking for places that could ensure Ben an education that would provide the tools for him to learn how to speak and learn properly.

The Foundation for Hearing Research consists of four main branches: Baby Talk, TeachLSL, Talk2Me, and The Weingarten Children Center (WCC).

One of these branches, the WCC is a school that specializes in teaching deaf children, specifically those around the ages of 2-8, and majorly benefits students on their road to college and overall education.

“When we visited WCC, we saw children who were talking and singing and were just like any other kids. That’s when we solidified our decision of implanting and going with the oral education,” Irene Rhazi said.

The school focuses on teaching the students what they would typically learn in preschool at a standard age, but they majorly emphasize the teaching of vocabulary, the pronunciation of words, and identifying objects with names.

“I think the best thing the WCC does for children who are deaf with cochlear implants is inviting them to a community with people that all share a common trait. It helps them feel like they’re not alone,” Ben Rhazi said.

The goal of the school is not to prepare students to go into other schools specialized in deaf teaching but rather to prepare them for the traditional education system where deaf students can be immersed into life with those who have no hearing problems.

From ages 2-6, Ben attended the WCC to learn the basic necessities for speech with speech therapists and other staff.

One of the speech therapists for Ben was Sharon Nutini, who has seen the benefits of teaching deaf students in a specialized way for the past 42 years.

“I worked at WCC for 42 years, my entire professional teaching life. I graduated from college and went directly to WCC, where I stayed until I retired in June 2023,” Nutini said.

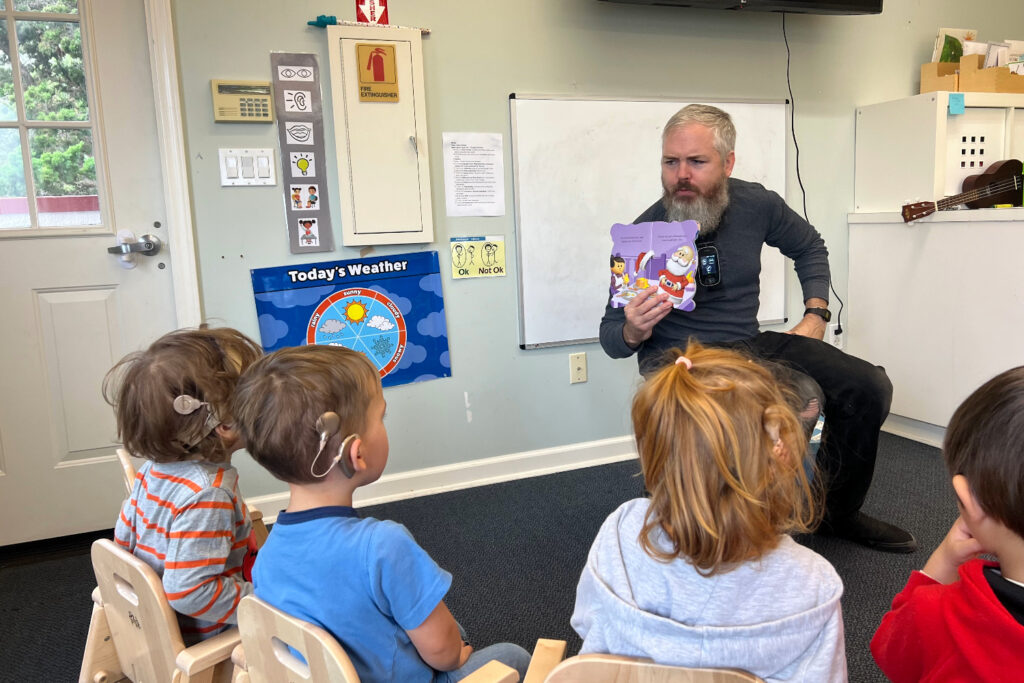

Teacher Matt reads a book to deaf children in the WCC to improve their reading, speaking, and listening skills. This is similar to Ben Rhazi’s experience in the WCC which helped him with writing, listening, and speaking.

Teachers and volunteers at WCC are what make it possible for Ben and students alike to receive the necessary education for their circumstances.

“Our cognitive curriculum is anything but basic. We teach our kids how to think outside the box, whereas most preschools don’t use this approach. Our kids learn how to compare, make analogies, and problem solve from very young ages” Nutini said.

After completing his years at WCC, Ben was immersed in the public school system.

However, even after receiving help with learning how to speak properly, many deaf children still find it hard to learn in the public education system, and this was true for Ben.

“Public school was very different from the WCC from what I remember,” Ben Rhazi said.

After Ben’s first few years of learning and navigating the public school system, his parents eventually decided the best course of action for him was for him to adopt an Independent Education Plan (IEP) for his years in public school. Once he reached the eighth grade, his parents decided he no longer needed the IEP as he had fully adapted to public school learning.

Throughout his childhood, Ben also played various sports, but once he reached high school, he focused on joining the football and lacrosse teams.

However, as Ben’s interest in sports rose, more hardships emerged. For football, he often found helmets would not fit correctly, and with any contact sport he played, there was always the chance he could accidentally break his cochlear implants.

“I have trouble with my implants all the time. I’m always going through something with them, usually it’s a broken piece or processor,” Ben Rhazi said.

In addition, he also found that the noise from the field and fans often combined to make it extremely difficult for him to hear coaches yelling instructions from the sidelines.

“I’ve played all sorts of sports throughout my life. The most general issue I’ve faced is not being able to hear communication on the field from teammates and coaches,” Ben Rhazi said.

However, despite the odds against him, Ben joined Hillsdale High School’s football and lacrosse teams and played for most of his high school years.

“It all comes down to who is the most talented or hardest worker out there,” Ben Rhazi said.

Ben excelled at academics and athletics during his high school career, partly due to his time at the WCC.

“Without the WCC, I wouldn’t be where I’m at now,” Ben Rhazi said.

Throughout his life, Ben has faced ups and downs regarding challenges because of his deafness, but whenever faced with problems, he has found a way to prevail using support from either his parents, the WCC, or friends.

“While there are challenges with being deaf, there is always a way around them,” Ben Rhazi said.